The first antibiotic, penicillin, was discovered in 1928 and first used to treat bacterial infections in 1941. This was just 80 years ago, so why are we seeing a rise in antibiotic resistance and “superbugs”? When I say “superbugs,” I am referring to organisms that have developed resistance to almost all known antibiotics. As we discussed in class, a big factor in this rise is the misuse (both intentional and unintentional) of antibiotics in general. Some examples of this would include: using antibiotics for viruses, not taking the entire dosage of antibiotics prescribed, and using antibiotics on crops and for cattle. Using antibiotics for cattle is beneficial, but only to the farmers selling these animals as it alters normal microbiota and promotes growth. This means a bigger check for them, but it puts the community at risk as it gives rise to antibiotic-resistant organisms, which can make their way into crops and spread into the community. Although there is bound to be antibiotic resistance among populations of bacteria due to random mutations or innate resistance, misusing antibiotics has definitely propelled the development of superbugs. The problems associated with these organisms are that they can spread among communities and are extremely difficult to treat.

THE CDC, WHO, and NIH do year-round tracking and research to identify emerging superbugs as well as how we can try to combat them. As of January 2020, the CDC has five bacteria and fungi listed as urgent threats, eleven as serious threats, two as concerning threats, and three on the CDC watch list (CDC 4). Two of those organisms are new to the list: Candida auris, a yeast, and carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter, a genus of gram-negative bacteria (Sun, n.p.). The main concern all the superbugs is that they are evolving quickly to resist the effects that antibiotics have on them, while we are making no progress in developing new drugs to combat them. It has been over three decades since a new class of antibiotics has been developed (Sun, n.p.). Another concern is C. difficile infections, which usually arise when people take antibiotics, a double-edged sword that kills good bacteria along with the bad, making us more vulnerable to infection. Superbugs alone are responsible for 2.8 million infections and 35,900 deaths, but when you add C. difficile to the numbers, it puts infections at above 3 million and death at 48,700 (CDC 6). These numbers are just a glimpse of the future to come if we were to completely lose the ability to use antibiotics. The burden it would have on global health would be extremely dangerous and we would see a lot more individuals dying as a result of once manageable infections.

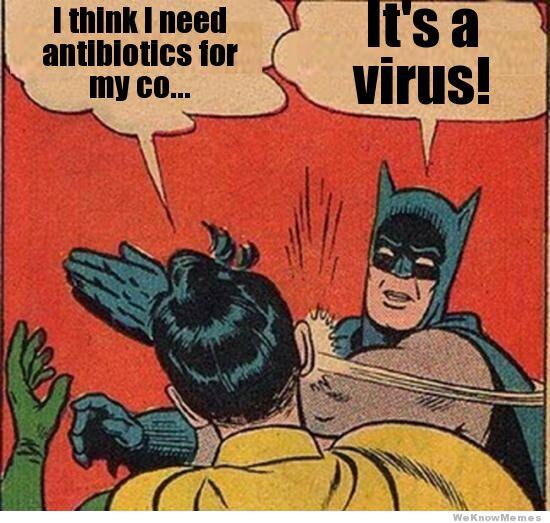

Now, a bit off-topic, but we’re going to move to Vibrio cholera. A recent study found that this bacterium can “steal” up to 150 genes from neighboring cells (Science Daily, n.p.). What this means for V. cholera is that it can change and adapt quickly. What this study doesn’t mention though, is how mechanisms like this are how antibiotic resistance occurs. Gene transfer is at the center of how organisms are able to “evolve” and dodge our modern medications. I hate to admit it, but bacteria are continuing to outsmart us and we are in dire need of more education and awareness about this issue if we hope to survive this post-antibiotic era. The corporation and actions of physicians, consumers, and government officials that have the power to impose more regulations on these miracle drugs are where we need to look to improve this growing issue. I’d like to end on a funny meme as I usually do, but considering the urgency of this issue, I’ll end with a piece of advice (it’s still funny too).